Words - Claire M. Bullen

No seasonal style – perhaps no other style of beer, full stop – is as controversial, as polarising, as simultaneously loathed and adored as pumpkin beer.

“Pumpkin is an abominable flavour that has no place in anything, let alone beer.” “I don't want my beer tasting like vegetables.” “Pumpkin has no place messing around with beer. Enough with this pungent, sickly taste in everything already!”

Within the last decade, pumpkin beer (technically pumpkin ale, in most cases) has enjoyed soaring visibility and widening reach. BeerAdvocate currently lists more than 1,300 examples of the style, and for many consumers – Americans, especially – its appearance on the shelves is as reliable a marker of the time of year as falling leaves and daylight savings. Even in Britain, where pumpkin beer has arrived much more recently, the style has been the subject of modest but growing interest. Influential breweries the likes of Beavertown, BrewDog and Camden Town have all experimented with pumpkin offerings.

But if its popularity has been widespread, its backlash has been even more so. Few, if any, styles seem to inspire the kind of vitriol that pumpkin beer does. People who hate pumpkin beer really hate it – they aren’t just happy to skip past it on the menu, they’re incensed that it exists at all.

“Never had one I remotely liked. Sickly thick dog sick more like.” “I don't want a goddamn orange latte, nor do I want a friggin' orange beer. It's not even ‘pumpkin’ flavoured. It's goddamn nutmeg and allspice and cinnamon in my fucking beer.” “Pumpkin beers and the whole Hallowe'en hype that has engulfed British society over the last 20 years or so has to one of the worst things that the US has exported to us.”

What is it about pumpkin beer that inspires these uniquely impassioned reactions? Could the style’s sweetness and spice be at fault? Perhaps it’s a rejection of over-the-top seasonal marketing? Or does the hatred go deeper?

I decided to find out.

Image courtesy of Buffalo Bill's Brewery used with permission.

***

To begin to understand the pumpkin beer backlash, it’s necessary to go back to the style’s origins. All the way back.

Many drinkers might be surprised to learn that pumpkin beer, often considered to be a contemporary trend, is actually several hundred years old. According to Cindy Ott, an Associate Professor of History and Material Culture at the University of Delaware and author of the 2012 work, Pumpkin: The Curious History of an American Icon, pumpkin beer has been an American staple since at least the 17th century. Before that, the pumpkin was a valuable food source for more than 10,000 years. “The pumpkin is the oldest domesticated plant, older than corn and older than beans,” she says.

Long before European colonists ventured across the Atlantic, Native Americans favoured the pumpkin for a few reasons. According to Ott, “You could dry it, it would last a long time, it was prolific, it grew like a weed, and the fruit was massive.” It was frequently roasted as well as dried, and served as a valuable food source when meat wasn’t available.

There are no early accounts of Native Americans making pumpkin beers; the first written records of brewing with pumpkins date to the 17th century. For early American colonists who struggled to survive the brutal winters and to plant successful crops in the New World, the pumpkin – and other Native American foodstuffs – quickly became a vital part of their diets, in beer as well as in food. Pumpkins were a cheap and plentiful source of fermentable sugars, though not always a very popular one.

Many early statements describe pumpkin beer as having an unappealing “twang,” Ott says, suggesting that its flavour was off-putting in comparison with other beers. In one account dating to 1771, a writer complains about the flavour of “pompillon ale,” though he concedes its taste improves after being cellared for two years. Another record from the 17th century says that beers made from “molasses, Indian corn, malt, and pompillons” were brewed by “the poor sort.”

“Pumpkin beer used to be a drink of last resort,” Ott says. “It wasn’t something that was valorised at all.”

But if the pumpkin was at first consumed out of necessity, it wasn’t long before it was adopted as a patriotic symbol. Particularly after the American Revolutionary War, early citizens saw the pumpkin as a symbol of American independence and self-reliance.

“The first published recipe for pumpkin pie was in the first American cookbook, which was written in 1796,” Ott says. “It was really a strong political text about Americans being orphaned and now being independent, and relying on themselves. It was the kind of story that the pumpkin could tell for Americans.”

That association evolved in the 19th century, when people began moving en masse to urban, industrial centres and were worried about being cut off from rural communities. The pumpkin again became symbolic, this time of an idyllic, bucolic way of life. “That’s when they start celebrating the pumpkin as something positive and virtuous,” says Ott.

By the 20th century, pumpkins were in the spotlight again. Halloween and Thanksgiving had both grown in popularity throughout the 19th century, ushering in the idea of the pumpkin as a festive commodity; whole pumpkins were purchased for decoration, while canned pumpkin was used in pie and other dishes. Once Americans began to own cars, they would drive to the countryside on weekends and pick their own pumpkins, straight from the patch.

“They buy [pumpkins] to tie themselves to these old agrarian myths, these stories that Americans still like to tell about themselves, and to make these personal connections with their kids and their families,” Ott says.

But what they weren’t doing, until very recently, was drinking pumpkin beer.

***

While jack-o’-lanterns and pumpkin pie were established hallmarks of autumnal Americana by the 20th century, pumpkin beer was, by then, a largely forgotten style. It wasn’t until 1985 – after home brewing was legalised in 1978 and the first wave of brewpubs and craft breweries were beginning to find purchase domestically – that pumpkin beer reappeared. The man to credit (or blame, depending on your tastes)? One Bill Owens.

Bill Owens founded Buffalo Bill’s, a California-based brewpub, in 1983. One of the oldest brewpubs in the country, it made just three beers upon its founding: a lager, an amber, and a dark. Owens, a serial entrepreneur, had also founded a magazine called American Brewer; in his free time, he read widely on beer history.

“I remember reading that George Washington used fruits and vegetables – including pumpkins – in his beers at Mt. Vernon,” Owens says. “I said ‘To heck with fruits and vegetables – I’m going to make a pumpkin ale!’” (For the record, Ott, when asked, couldn’t verify this account about George Washington, though she noted it was a possibility.)

Owens went out and bought a twenty-pound pumpkin at his local supermarket, which he roasted and added to an amber ale mash. After pitching the yeast, he allowed it to ferment for a few days before sampling.

“So I go to taste it, and there’s absolutely no pumpkin flavour whatsoever. And I said wait a minute – a pumpkin doesn’t have cloves in it. A pumpkin doesn’t have cinnamon in it. A pumpkin is a gourd – and a gourd is neutral.” To solve the problem, he went back to the supermarket and bought a can of pumpkin pie spice mix, which he percolated with water in an electric coffee maker before adding to the beer.

The experiment worked. “It was a pretty big hit,” Owens says.

Little did he know at the time, but his pumpkin beer was about to kick off one of the most controversial beer styles in recent memory.

Image via Yelp-Inc on Flickr. Published under a Creative Commons license.

***

Owens’s recipe brings us to one of the first major complaints about pumpkin beer: that the flavour we associate with “pumpkin” isn’t related to the gourd itself. Rather, it’s a spice mix of cinnamon, nutmeg, clove, ginger, maybe cardamom and allspice, that has been used to gussy up the mild pumpkin, and has since become a proxy for pumpkin flavour. Many pumpkin beers, detractors say, are little more than cleverly marketed spiced beers, only described as “pumpkin” in order to piggyback off the pumpkin spice trend that’s become unavoidable every autumn.

It’s true that pumpkin products are more ubiquitous now than ever before. A recent article highlighted dozens of pumpkin spice-flavoured foods and drinks that are sold in American grocery stores, ranging from English muffins and chewing gum to hummus and soya milk. The craze has inspired celebrity chefs the likes of Anthony Bourdain to rail against the cult of pumpkin spice, while food writers have penned obscenity-laced tirades directed at the trend.

The excess of pumpkin flavoured products elicits a uniquely negative reaction in some consumers, Ott says. “You don’t get this strong reaction with eggnog flavoured or cranberry flavoured [foods and drinks]. And I think it’s because of these deep meanings that people associate with pumpkin […] because it’s supposed to be these core American values and then you’re commercialising it.”

If the crass ubiquity is an issue, many also see the lack of real pumpkin in pumpkin-flavoured foods and drinks as an affront, if not an all-out betrayal. Last year, consumer criticism was strong enough to inspire Starbucks to change the recipe for its infamous Pumpkin Spice Latte; it now includes real pumpkin. In the beer world, this criticism is focused on pumpkin beers that don’t contain any pumpkin, and which use only spices as their flavouring agents.

Is that critique fair? In a historical context, perhaps not. “[Spices] are the flavours that get associated with the pie, and the pie is associated with these celebratory values and ideals about this nurturing farm life,” Ott says. “So it’s those values that are in the pumpkin and – because pumpkin doesn’t taste like anything – in those spices that are associated with it.”

For a brewer making pumpkin beers, the choice to lead with a spice-heavy recipe may also be a pragmatic one. “I was always up-front about using spices as an additive,” Owens says, “and anybody that tells me they’re getting those kinds of flavours out of a pumpkin ale without adding spices is lying to you!”

Nathan Arnone, a brand manager for Southern Tier, echoes Owens’s statements. “The problem with pumpkin is by itself it is rather bland. It’s only from the spices that it becomes truly delicious. Many variables exist when it comes to brewing with spices, and getting it correct is easier said than done.”

But Pumking – Southern Tier’s imperial pumpkin ale, and one of the most popular pumpkin beers on the market – is still brewed with “literally tons of pureed pumpkin” in addition to the spices, while Buffalo Bill’s Pumpkin Ale features “baked organic pumpkin” alongside the cocktail of spices, according to current CEO and Master Brewer Geoff Harries, an addition which he says yields up “an earthy flavour”. For the record, many pumpkin beers do contain actual pumpkin alongside the spices. If nothing more, brewers seem savvy enough to recognise that pumpkin beer sans pumpkin can be a PR misstep.

***

It isn’t just the omnipresence of pumpkin spice that many consumers reject, however. As beer writer Chris O’Leary, of the New York-based beer blog Brew York, says, it’s also an issue of so-called “seasonal creep.”

“Seasonal creep is essentially the result of a race to debut pumpkin beer first,” he explains. “When pumpkin beer first took off about half a decade ago, breweries started rolling out their seasonal beers earlier so they could be first to market and get better distribution and visibility of their product. First it was August when we started seeing it. Now it’s July. And last year, I think consumers finally reached their limit.”

As a truly seasonal product, part of the magic of the pumpkin is its ephemerality – consumers who love pumpkin look forward to the autumn as the time they can enjoy it, much as peach lovers wait eagerly for late summer and asparagus geeks get excited about early spring. Pumpkin in July feels unnatural to American consumers primed to see the pumpkin as the ultimate autumnal symbol. It’s also a bigger problem for breweries that make other seasonal styles throughout the year.

“Seasonal creep is problematic, especially now that it’s spread to all seasons, because it leads to the breakdown of a calendar that uses fresh seasonal ingredients,” O’Leary says. “Harvest beers that use fresh hops from the year’s harvest can’t be released in late September because that’s now nearly two months late for a fall seasonal beer. And as with pumpkin beer’s glut last year, consumers don’t want to buy winter warmers in October or lighter spring beers in January. Beers sit, and when consumers actually want to drink them, they’re not as fresh because they’ve been sitting on the shelves for two months.”

For his part, Arnone places the blame on retailers, rather than the breweries themselves. “Although nobody wants to hear it, the reality is when retailers and wholesalers ask for a product to be delivered, it had better be delivered,” he says, which puts breweries in a bind.

Whether it’s ultimately the fault of retailers and distributors or the breweries seeking to out-gun each other, seasonal creep may be playing a significant role in turning consumers off the style.

Image courtesy of Elysian Brewing used with permission.

***

“I don’t know why there’s a backlash,” Josh Waldman, the Head Brewer at Elysian, says. “Maybe it’s the patriarchy.”

Beyond its ubiquity, its unseasonal appearance on the shelves, or its ingredients, there’s another – more troubling – component to pumpkin beer antipathy: its perceived target demographic. I noticed a telling trend when I polled a group of fellow beer drinkers about who they think of as the “typical” pumpkin beer drinker:

“Women who are with their guy and want something different.”

“Women and foodies who appreciate highly seasoned beers. Most men I know are not fans of pumpkin beer.”

“Typical white girl trash.”

“White women?”

“22-40 year old, high school or college educated white female. Sorry if this is harsh!”

“White single girl in her thirties wearing yoga pants trying to impress a guy.”

“All I can think of are annoying sorority chicks waiting in line at the Starbucks drive-through for pumpkin spice lattes. The beer is for the rest of us, I guess.”

“Someone who owns a ton of clothes from Abercrombie & Fitch, has pre-ordered the new iPhone and loooooves poodles.”

In other words: the perceived typical pumpkin beer consumer, like the Pumpkin Spice Latte drinker, is a “basic bitch.”

The idea of the basic bitch is, by 2016, well-trodden internet turf. If there’s any singular, prevailing marker of someone who’s “basic,” beyond her predilection for wearing Uggs and love of the autumn, it’s her obsession with pumpkin spice lattes (and everything else pumpkin).

“It is the setup to nearly every now-familiar punch line about a basic bitch, her love for the autumnal mass-market beverage. Pumpkin Spice Lattes are “mall.” They reveal a girlish interest in seasonal changes and an unsophisticated penchant for sweet,” Noreen Malone writes in New York Magazine. “And the basic bitch […] is almost always a she.”

Much of the anxiety surrounding the Pumpkin Spice Latte – and, by extension, pumpkin beer – can be read as anxiety about patterns of consumption, about how the products we consume also function as an external signal to others about the kind of person we are.

What do pumpkin products signal? For many, they demonstrate unsophisticated taste, girlishness, the opposite of connoisseurship. And, as with white wine, fruity cocktails, and other drinks that are still classed as “girly drinks,” they’re profoundly uncool for men to consume (this notably doesn’t work in reverse; women are often lauded for consuming historically male-gendered products, like whisky and hoppy beers).

This might help explain why pumpkin beers are frequently reviled in male-dominated craft beer circles, while other sweet, adjunct-heavy styles are, comparatively, revered. Beers the likes of Westbrook’s Mexican Chocolate Cake, 3 Floyds’s Dark Lord, and Cigar City’s Hunahpu are some of the most sought-after bottles today, yet all three are sweet, high in alcohol, and feature dessert-y adjuncts ranging from vanilla beans and cacao nibs to cinnamon and Indian sugar. Is the problem with pumpkin beer really a problem with sweet, spiced styles?

Even pumpkin-phobic British drinkers may be traditionally primed to enjoy spiced beers, explains Jenn Merrick, Beavertown’s Head Brewer and Director of Operations. “It’s funny cause the British tradition for Christmas beers definitely includes cinnamon and things like that – I’ve worked in traditional cask places, where we put cinnamon and nutmeg in every Christmas.”

For some consumers, a general aversion to sweet or spiced beers is a legitimate flavour preference. But for others, the knee-jerk hatred of pumpkin beer, whether conscious or otherwise, may signal something deeper and more problematic.

***

What’s next for pumpkin beer? Even while pumpkin spice products are proliferating on the shelves and pumpkin beers are migrating across the sea, some are arguing that the style’s peak has already passed.

“I think we’re already seeing its decline,” O’Leary says. “It’s possible that 2014 was Peak Pumpkin Beer.” Earlier this year, O’Leary wrote about declining pumpkin beer search volumes, as well as a glut of pumpkin beers that were left on shelves last year. This year, breweries like Alaskan Brewing are eliminating pumpkin beer from their autumn line-ups in favour of new seasonal styles, in the hopes of distinguishing themselves from the sea of pumpkin. And they’re not alone: following flat sales last year, other breweries – Southern Tier included – are reportedly scaling back on their pumpkin offerings.

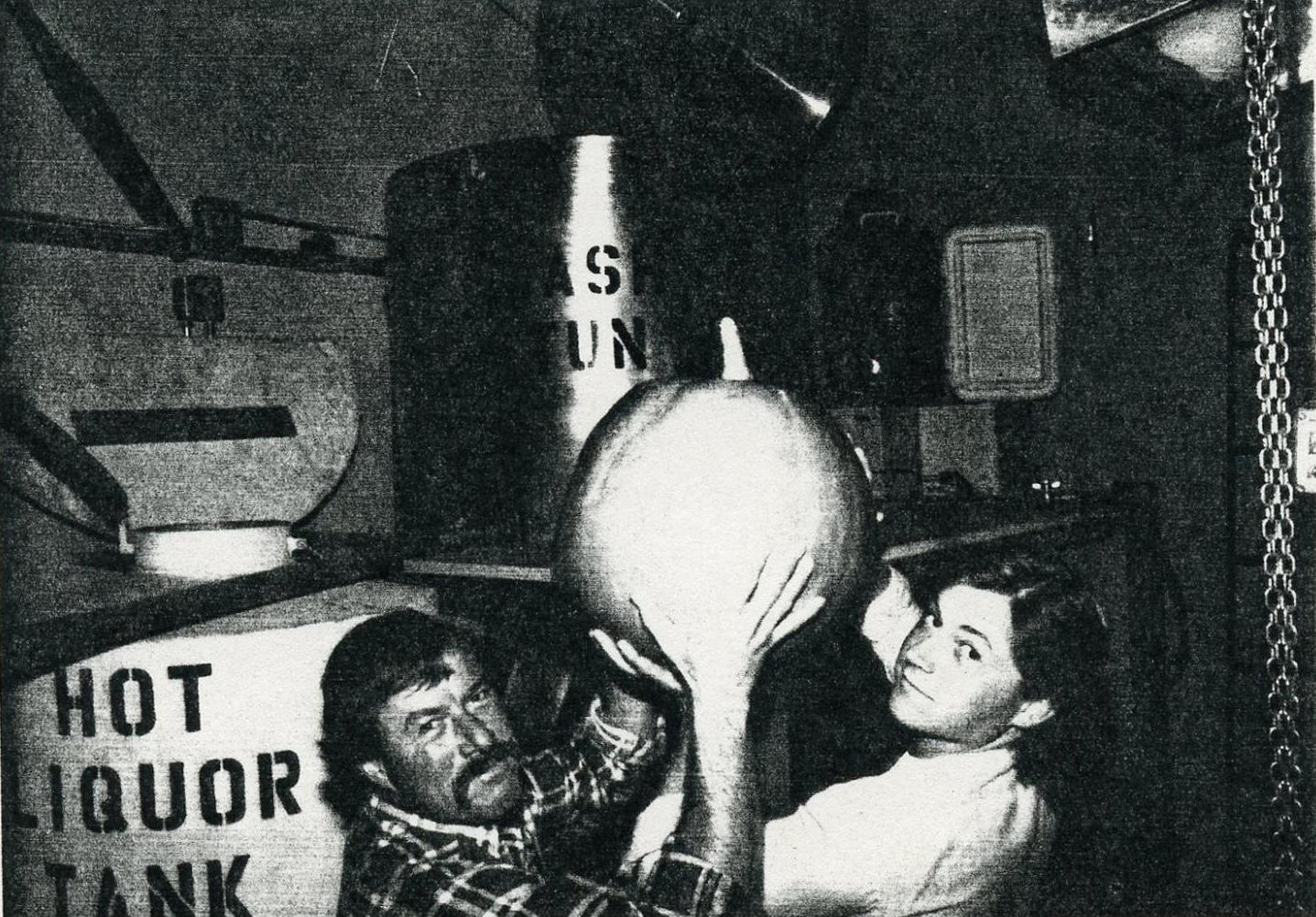

But while some are cutting back, others are continuing to push the boundaries of the style. At Elysian, Waldman has made it a particular mission to grow the brewery’s pumpkin line. Elysian currently makes four pumpkin beers for distribution on an annual basis (a classic pumpkin ale, a pumpkin stout, an imperial pumpkin ale, and Punkuccino – a pumpkin beer modelled on the Pumpkin Spice Latte), and brews many more small batches for its annual Great Pumpkin Beer Fest. The festival, which is celebrating its 12th anniversary on October 8th, will feature upwards of 80 pumpkin beers sourced from 60 US breweries, in addition to a several-hundred-pound pumpkin that has been jerry-rigged to dispense pumpkin beer. Elysian alone brews at least 20 pumpkin beers for the occasion.

“It was almost a lark at first, and has sort of spiraled into this fun, crazy, ‘let’s see how far we can take this’ sort of phenomenon,” Waldman says.

He also reports that, as far as Elysian is concerned, demand for pumpkin beers has only increased. “It’s become a seasonal rite. Pumpkin spice is its own ‘season’ now.”

But Waldman points out that, despite the pumpkin plenitude, we still haven’t seen the full potential of the ingredient yet.

“In most parlance, what we talk about when we talk about pumpkin beer is something of the pumpkin pie spiced variety,” he says. “Though for Elysian, and many others, pumpkin isn’t a style; it is, of course, an ingredient. An ingredient that can be used to brew just about any existent style of beer. This is playing out in the popular market space for pumpkin beers, as the category evolves to include stouts, sours, and imperial pumpkin beers.”

It’s true that, for those seeking non-traditional pumpkin beer offerings, there are more choices now than ever. New Belgium brews Pumpkick, a lightly tart beer that also features lemongrass and cranberry juice. Timmermans’ Pumpkin Lambicus is a surprising, Belgian take on the trend. 21st Amendment makes two subtly pumpkin-spiced versions of He Said, one a Belgian-style pumpkin tripel and one a pumpkin Baltic porter. Avery’s Pump[KY]n takes a pumpkin porter and ages it in bourbon barrels, while its Rumpkin adds an imperial pumpkin base to rum barrels.

In the UK, Beavertown – who started making Stingy Jack, their pumpkin beer, three years ago – are also thinking beyond the classic pumpkin spice format. “We’ve been playing with this idea of a sour beer with pumpkin in it,” says Merrick. “If we have any pumpkin left at the end of season – we do a lot of lacto-sour beers, kettle sours – we’ll play with souring a bit of wort with some pumpkin thrown in, and just see where we could go with that.”

Perhaps the key to pumpkin beer’s endurance – and to winning over pumpkin skeptics – is to follow Waldman’s lead, then, and continue to diversify the pumpkin offerings on the shelves beyond the overabundant pumpkin spice format. When we consider pumpkin as an ingredient rather than a single style, all kinds of new, creative potential is revealed.

“Craft beer doesn’t belong to anyone, so why should anyone get upset if people like to brew with pumpkin?” Waldman says.

It’s a fair point. Me, I’ll toast it with a fresh pint of pumpkin beer.